Was Gassy Jack’s Statue Toppled By His Courageous Wife?

Quick Summary

- Gassy Jack Deighton’s statue was toppled in 2022 amid outrage over his marriage to Kwa7xiliya (Madeline), a twelve-year-old Squamish girl and niece of his late first wife

- Kwa7xiliya’s story reveals she was cheated out of her inheritance after Deighton’s death, and ultimately returned to her people to rebuild her life, remarrying and having more children with her new husband, an Indigenous man

- Remembered as a resilient and strong-willed woman, Kwa7xiliya lived into her nineties and is now recognized as a key historical figure deserving her own place in Vancouver’s story

The man stood on a barrel, a rope around his neck. Cheers rang out as the rope tightened. Man and barrel teetered, then quickly crashed dramatically to the ground. “Gassy” Jack Deighton, Gastown’s namesake, was literally and figuratively knocked off his pedestal when his statue was toppled during the Downtown Eastside Women’s Memorial March in 2022.

“It felt like good medicine,” said a woman who was there that day. But why so much anger at a voluble publican whose dubious legacy was to build the area’s first pub and then die in debt? The answer lies in the woman Deighton married, a young Squamish woman known as Madeline… and also by her real name, Kwa7xiliya, or Quahail-ya.

Gastown’s Maple Tree Square in 1886. The large maple tree is close to where Gassy Jack’s statue would eventually stand. Photo courtesy COV Archives AM753-S1-: CVA 256-06

Gassy Jack’s Teenage Bride

Many details of Kwa7xiliya’s story are lost in the past, but it’s agreed upon that she crossed the water to care for her ailing aunt in Granville (later known as Gastown) around 1870. The aunt was married to Gassy Jack Deighton and when she died, he married Kwa7xiliya. In her own words:

“…after a while she sick, my aunt, Gassy Jack’s wife, and she die; long time ago; I not stop long Gastown; be about twelve when I was Gassy Jack’s wife; then Gassy Jack die, too, and I come over to here” (North Vancouver); “then come to my brother and my sister.”

It’s Kwa7xiliya’s words here that sparked much of the future anger towards her husband, because as she herself says, she was only “about twelve” when she married Deighton. Cue the justifiable outrage. But being outraged about Gassy Jack Deighton marrying a teenager still obscures Kwa7xiliya’s own story.

Cheated Out of Her Inheritance

She must have been a tough woman. At around twelve years-old, living away from her people, she suddenly had to care for the rough ex-sea captain who now dealt in selling liquor to the working men of Granville. A newspaper article published in 1886 refers to the fact that Kwa7xiliya would leave for home several times a month, suggesting that she may have found life with her new husband to be less than satisfactory.

James Matthews, a prominent local historian and Vancouver’s first archivist, interviewed a Mrs. James Walker about Kwa7xiliya in 1940, and she had this to say:

“…gee, she was a pretty lady. She told me there was money left to her and her son, but she never got it. When his brother and his wife came they took charge of everything, and she went back to her people. Then, she said, Gassy Jack died and her son died about a year afterwards. She told me that Gassy Jack left a will for her to get money, but she never got it, and they buried him in New Westminster.”

Intrigued by Mrs. Walker’s memories, Matthews tracked down Kwa7xiliya herself just a month later and talked to her, first through younger family members who interpreted, and then to “Madeline” herself. Kwa7xiliya’s English wasn’t perfect, but she remembered her former husband and her short-lived marriage well enough:

“No steamboat come; no white man; just one house; Gassy Jack came in big canoe”—and she waved her arm indicating from the direction of Port Moody up the Inlet—“then Gassy Jack go Westminster to run steamboat up to Port Yale…and my aunt she go over to New Westminster and live there so when he come back to Westminster be there when he stopped his steamboat. Gassy Jack about your size” (five foot eight and a half); “nice good man; then he come Gastown, make great big hotel.”

Whether or not Deighton really was a “nice good man” to Kwa7xiliya, his death meant a return to her people, and eventual remarriage to an Indigenous man. Archivist Matthews, in an attitude very typical for his time, was less excited about meeting an Indigenous woman who had seen so many dramatic changes to the area in her 90-odd years of life, and far more excited about being able to:

“…touch the person, of a wife of John Deighton, alias “Gassy Jack” of Gastown, the historic whiteman to establish himself in Granville, now Vancouver.”

“A Woman Of Strong Character”

Kwa7xiliya lived until 1948. Her story lives on through members of the Squamish nation, as well as a few photos and interviews. Canadian painter Mildred Valley Thornton painted her portrait in 1946, two years before Kwa7xiliya’s death, and described a woman who was still “stubborn as a mule,” who had been in her youth “a woman of strong character and decided convictions.” (However, she also describes Gassy Jack as having been “a thoroughly good citizen,” whereas other descriptions of the man suggest that Deighton seldom met a law or rule he minded breaking, or at least bending.)

According to Thornton, Kwa7xiliya “could not endure the smell of whiskey,” and it was for this reason that she up and left the life of a bartender’s wife and returned home. Perhaps she was also mourning her little son, who must have been well-loved because he was known as the “Young Earl of Granville.” Sadly, he died as a toddler.

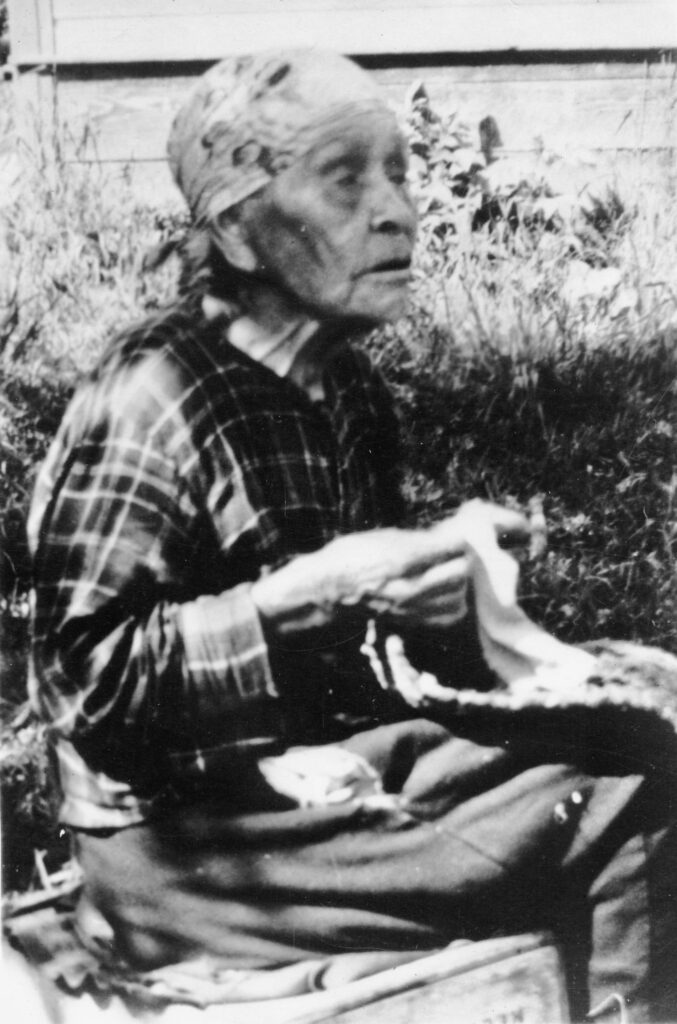

Kwa7xiliya, or Madeline Deighton, late in life. Photo courtesy of COV Archives AM54-S4-: Port P786.1

Kwa7xiliya had other children with her second husband. Her life was hard, but she was a tough woman, and was at least 90 when she died, having outlived her first husband by seventy-three years. In their obituary, The Vancouver Sun called her the “first lady of Vancouver.” A fitting title for the strong, stubborn woman who, as Squamish chief Ian Campbell recently said, deserved her own statue alongside Gassy Jack’s.

Take Forbidden Vancouver’s Lost Souls of Gastown tour and learn more about Kwa7xiliya and the history of Gastown!

You can find John Deighton’s grave in Fraser Cemetery, New Westminster. Photo courtesy of the Vancouver Sun.

My name is Alison Jenkins and I’m a musician, a songwriter, and a tour guide with Forbidden Vancouver. Born in Toronto, I moved here with my family when I was 14 years old. Let’s dive into the history of Vancouver together!